South China Sea : Contesting Narratives and Global realities

The developments in the last five years in South China Sea has gained international attention following the Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) ruling in favour of the Philippines. The ruling clearly stated that the China’s claim of nine dash line and the proclamation of Exclusive Economic Zone for the islands in South China Sea is not acceptable under the provisions of international law and UNCLOS 1982. Subsequently, the Philippines sensing that the international community is not pressurising China to accept the ruling of the PCA changed its stance and started gravitating towards China to seek certain concession and protect its marine assets in the contentious region. The negotiations about Code of Conduct (CoC) in South China Sea also gained momentum and it was perceived that China might accept certain regional norms and a standard operating procedure might be accepted. The draft COC has become large in content and the possibility of a common consensus died when China started propagating that it would prefer bilateral negotiations with other claimants rather than accepting the multilateral negotiations.

Meanwhile, US started group sails and undertaking surveillance and reconnaissance mission in South China Sea closer to the Chinese controlled islands leading to tensions between the two powers. Vietnam as well as Malaysia and other ASEAN claimants submitted their representation regarding extended continental self which as supported by the European powers and the US. The diplomatic statements and the need for accepting maritime security as a critical issue sled to frictions between US and China in different forums including Shangri la Dialogue, ADMM plus and East Asian Summit meetings too. The role that ASEAN played was subdued and tried to bring more sanity between various contesting parties. The statement became more focussed, however, desisting from naming China in the joint communiques.

The institutions in Southeast Asia reflect the concerns of the major claimants. The Chinese fishermen militia and increased Chinese military modernisation led other claimant countries to upgrade their navies and coast guards. There was a surge in submarines procurements and developing fighter aircrafts fleet among countries such as Vietnam and Indonesia. The maritime survey ships of China, at multiple time infringed the EEZ of the littoral countries, and intimidated the patrol ships through water cannons, and at time even destroying the fishing boats of other countries. This was followed up with unilateral fishing ban of three months in the contested region.

Increased military tensions in SCS was followed up with European powers dispatching their ships in the South China Sea in the year 2021. The tensions between the two powers - China and US, and the Philippines government accepting the fact that cajoling China would be of no help accepted the fact that US Visiting Forces Agreement (VFA) need to be maintained for maritime security of the country. ASEAN also adopted its outlook towards Indo-Pacific construct and one of the important salient points has been maritime security which would help the countries to engage the major powers in a constructive way while securing the maritime trade and commerce, and unimpeded flow of energy, and other critical resources in the region.

The US along with other Quad countries started working on maritime security architecture and created the Quad forum at the highest level to address issues related to Chinese aggressive posture and intimidating tactics. The effort was to counter Chinese BRI initiative and providing the alternative configuration and plan which is now better known as Build Back a Better World(B3W)-an initiative undertaken by the G-7 countries.

During the chairmanship of India in the UNSC special discussion and dialogue was held highlighting maritime security which addressed concerns of major powers and the Vietnamese Prime Minister made a fervent call for UN institutionalized support structures in the regional context to frame the rules of engagement and protect the interests of smaller countries in South China Sea.

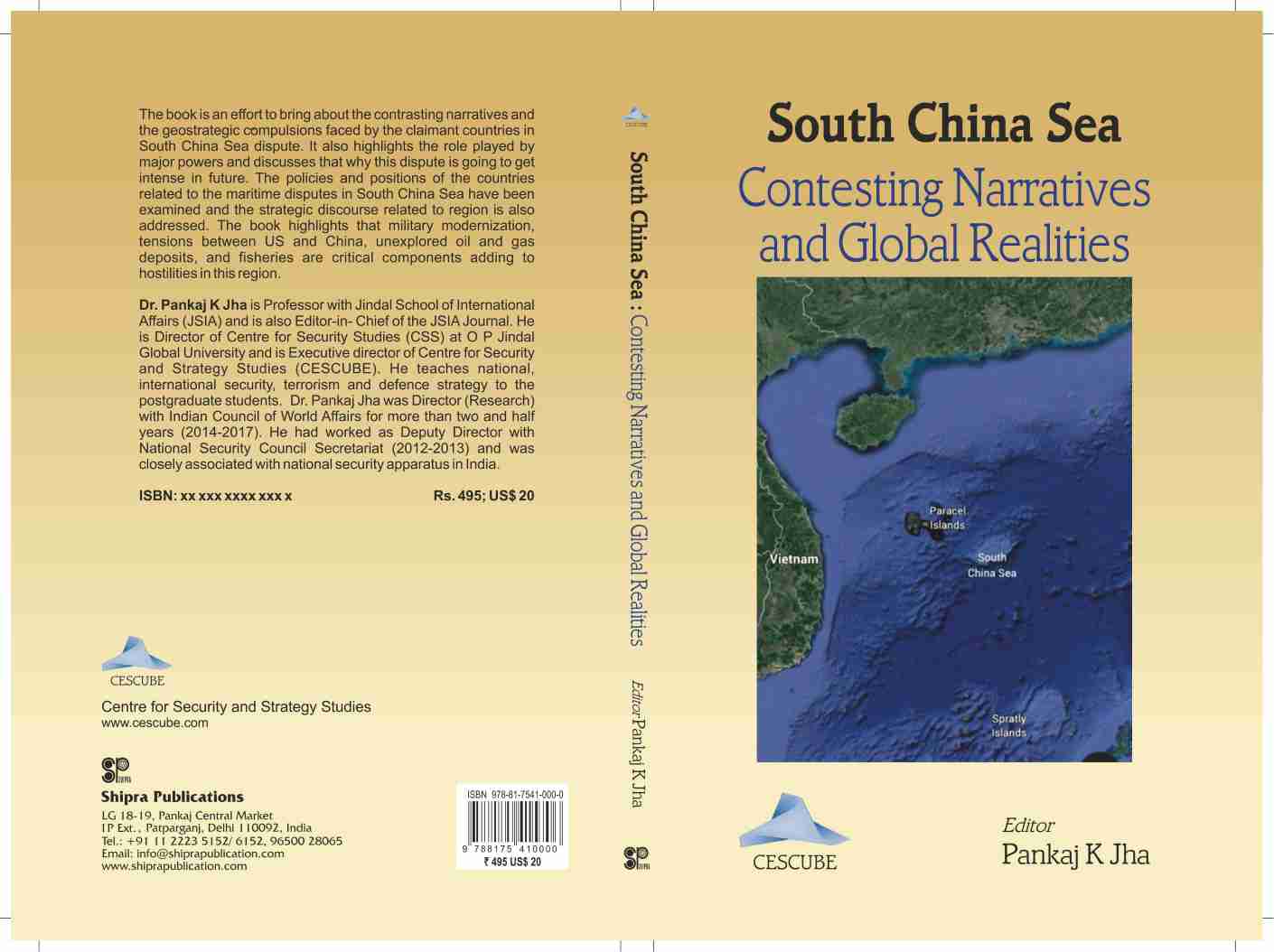

This book aims to highlight the narratives which are germinating from China, ASEAN countries, Japan, and other relevant stakeholders. The book also highlights the fact that China’s newfound interest in South China Sea does not have major historical backing (as illustrated in the maps in the book) and therefore South China Sea, the third largest fishing grounds in the world and has immense energy resources, should be seen as a major flashpoint and the theatre of international power politics in future.