The outbreak of coronavirus, labeled by the World Health Organisation as COVID-19, in the Chinese city of Wuhan and now spread to more than 70 countries has shaken the world, upsetting the world’s capital markets and severely impacting inter-governmental relations between countries as they make every effort to contain its further spread. Official estimates tell that more than 3,000 people have already lost their lives, though unofficial figure could be many times the number. Though several commentaries on this issue have already occupied space in media outlets, both on and off line, this commentary focuses how Japan is coping with this menace.

The first political fallout of this is the cancellation of Chinese President Xi Jinping’s planned state visit to Japan in early April, as both Japan and China focus on fighting the coronavirus outbreak. Both sides have agreed to reschedule the visit around autumn when Prime Minister Abe Shinzo and Emperor Naruhito have openings in their calendars. A state visit would include a meeting with Emperor Naruhito and a banquet at the Imperial Palace. Meetings with the Japanese emperor must usually be finalised a month in advance.

Earlier on February 28, Yang Jiechi, a Chinese Communist Party Politburo member and the nation’s top diplomat, held meetings with Japanese government officials to lay the groundwork for the visit. The following day, Abe announced the postponement of the visit at a press conference, noting that Chinese Presidents tend to visit Japan only once in a decade and that Japan needs to ensure the trip bears fruit. The last state visit by a Chinese president was by Hu Jintao in May 2008.

Given the historical irritants and China’s aspiration to regain its lost glory, the two governments are keen to define a new era in bilateral relations ahead of Xi's planned visit. Both are serious to work towards the creation of a major political document, the fifth of its kind since the countries normalized diplomatic relations in 1972. The coronavirus outbreak that originated in China and now spread into Japan has thrown a monkey wrench into the diplomatic schedule. Though the coronavirus cases in China have begun to slow down, infections in other countries have risen sharply, raising concerns about a possible worldwide pandemic.

Though both governments agreed to reschedule the visit, stronger opposition to the visit emerged within the government and Abe’s Liberal Democratic Party, especially among conservative lawmakers who argued that major issues ranging from China’s maritime assertiveness to the human rights situation in Hong Kong remain. The shadow of history does not easily go away, throwing perpetual challenge to the leaders at the helm to mend fences.

The pneumonia-causing virus spread rapidly globally from its epicentre in Wuhan, central China. New South Korean cases exceeded those in China for a third straight day and included a 45-day-old boy. In fact, South Korea has emerged the country with the highest number outside China, after infection cases skyrocketed. The United States, Australia and Thailand all reported their first deaths from the epidemic, while Ireland and Luxembourg reported their first confirmed cases. Cases have been reported also in India, though no one has succumbed to death because of the virus. There is no vaccine as of now, though scientists are working on it. Even if they are successful, it would take many months more to be available in the market.

With a view to contain its spread, The Abe government lost no time in taking countermeasures. Though Abe announced a closure of schools across the nation, this was met with scepticism, even criticism, by healthcare experts, educators and parents, confused by the move. Experts opined that Abe’s move could be counterproductive. The biggest problem in Japan is that nobody knows how widespread the COVID-19 outbreak has become when numbers no longer provide an accurate gauge of the situation. Critics questioned the number of infected patients, excluding those infected onboard the Diamond Princess cruise ship, saying that the figures do not signal cause for alarm at first sight. However, the government does not want to take chances as the number of hidden cases could suddenly bubble the surface.

Though Japan had come under fire for lax hospital rules on patient movement in the initial stages of the outbreak, South Korea ramped up countermeasures including testing, making rapid diagnostic tests available at 50 healthcare facilities and tested over 85,000 suspected infected persons in contrast to 2,517 tests undertaken by Japan, growing concerns that opacity marks the true scale of the outbreak in the country. Even if Japanese government revamps the healthcare emergency response system, the demand for more robust disease management measures need more strengthening.

The decision to close schools from March 2, an unprecedented move, was not met with warm reception but outrage as parents, local governments and school administrators were not consulted and therefore were caught by surprise. There is a perception in Japan that Abe has an eye in building a legacy as his term as prime minister conclude in September 2021 and therefore he sensed the national mood before taking some form of swift, decisive action to demonstrate leadership in a time of crisis. But critics say Abe’s decision to close schools was flawed, arguing that if his decision was to protect children, why did he leave out nurseries, kindergartens and after-school facilities? The perception growing ground that while other neighbouring countries such as Hong Kong and South Korea are upfront in their measures to protect the vulnerable children from the spread of the virus, Japan was seen wanting in reaching out a national consensus on how to deal with a severe national situation.

Abe’s measures are seen as a knee-jerk reaction as he was expected to explain to Japanese families the outlook for the country and rationale for his move but he did not, which is why experts question the merit of his decision. CNA report observes thus: “Infectious disease specialists, like Head of the Kawasaki City Health and Safety Research Centre Nobuhiko Okabe and Masaki Yoshida, professor at the Jikei University School of Medicine who chairs the Japanese Society for Infection Prevention and Control, expressed skepticism over the decision to impose a uniform closure of schools, which did not consider differentiated regional infection levels and whether schools have seen clusters.â€

The third fallout of the virus breakout is whether Tokyo shall stick to hold the Olympics. At the time of writing this, there are conflicting versions of opinions. According to a senior member of the International Olympic Committee if it proves too dangerous to hold the Olympics in Tokyo this summer because of the coronavirus outbreak, organizers are more likely to cancel it altogether than to postpone or move it. A lot is at stake during this critical period between the time how the spread of the virus is contained and plan to host the event remains. Abe has a great sense of responsibility and his political leadership to address this new situation will be tested.

Abe seems to be losing political trust fast. His declaration to set up a reserve fund of 270 billion yen (US$2.5 billion) without specific steps on how to cope with the situation did not cut any ice. On the contrary, it stoked fears that the government would again roll out new, disruptive plans that would leave healthcare experts, parents and the public caught on the backfoot. Abe could be under pressure to hold on to his post. As mood of frustration hangs over Japan, demand for his resignation could rise. The onus now is on Abe how he restores public confidence that shall help him to cope with the new unexpected situation to keep the virus away from Japan. Japan also faced criticism for its handling of the cruise ship. Multiple new cases emerged while the ship was in quarantine and among passengers allowed off the ship after initially testing negative. The private sector is more cautious. Japan’s ​​​​​​​biggest trading firm, Mitsubishi Corp, for example, asked all of its 3,800 staff in the country to work from home for two weeks.

Even when the virus continues to spread, pressure builds up on Abe to handle the situation with urgency and seriousness. Critics are asking "Where's Abe?" The general perception is that instead of taking the lead to handle the situation himself, Abe has left the task largely to his Health Minister Katsunobu Kato. His political support base is already being eroded. A recent newspaper survey showed disapproval for his administration outweighing approval for the first time since July 2018. In this situation, Abe’s dream of winning a rare fourth term at the September 2021 end of his tenure as ruling party leader could soon turn out to be a mirage.

Japan drew heavy criticism for its handling of the virus outbreak on the UK-registered cruise ship Diamond Princess since the vessel docked near Tokyo on February 3. While some other countries took stiffer steps quickly, Japan faltered. While Italy emerged as a new frontier in the fight on the virus by sealing off its worst affected towns, closed schools and halted the carnival in Venice, and US President asked Congress for US$ 2.5 billion to fight the virus, Japan’s allocation of $92 million (Yen 10.3 billion) from budget reserves gave the impression that Abe was in denial and believed in the most optimistic scenario. Social media critics questioned why Abe did not close Japan’s borders to all Chinese visitors instead of just those from the central province of Hubei, whose capital Wuhan in the epicentre of the epidemic, and the eastern province of Zhejiang.

Critics opined that Abe was too keen to host Xi and therefore did not want to displease him by taking stiff measures to contain the virus. The fact that Japan’s economy is heavily reliant on Chinese tourists in recent years must have weighed in Abe’s calculation. It is also possible to believe that Abe was trying to minimise the number of those infected to ensure that the Olympic remains on track. For Abe, the Olympics which run until August 9, unless cancelled or postponed, is a key goal of his administration. Hit by the consumption tax increase in October 2019, the economy has already headed downhill with depressed consumer spending. Now the spread of the virus chills activities further, raising the risk of recession. If the economy tanks further and does not get a boost from the Olympics as Abe expects, that is going to be catastrophic and lay the ground for Abe’s political demise. Abe faces tough choices.

-------------------------------

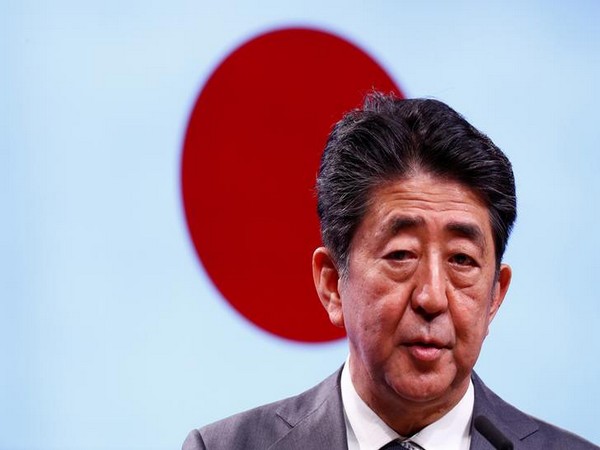

(Pic Courtesy -ANI News )

Professor Rajaram Panda, a leading scholar on Indo-Pacific affairs, is currently Lok Sabha Research Fellow, Parliament of India, and a Member of Governing Council, Indian Council of World Affairs, New Delhi. E-mail: rajaram.panda@gmail.com