Privatization of the ISRO - Critical Security Concerns

The recent debate started among the Indian policy makers and academicians what would be impact of the government decision regarding the entry of private players in the space sector. Most of them are in favour of the government initiative for growth and development of the space sector. For India, the issue of space technology has always remained with critical aspects. It had taken many steps to develop the advanced and competitive technologies to achieve the economic, security and strategic goals. Allowing the private players’ investment in the space sector is one of the steps which would help to develop its capacity. There are some questions that need to understand. What are the factors that compelled India to allow private players in the space sector? What will be method of the private player’s engagement in the space sector? What will be benefits and risks of private companies’ investments? Before answering these questions, we have to understand the private companies’ engagement of other countries like US, Russia, China and France.

United States is one of the countries that has permitted private players in the space sector. The engagement of private players in the US was started during 1960s, that provided the opportunities of the US government agencies to understand the working behaviour and the significance of the private players for growth of space sector. Since then, the US has passed various acts and reformulated the space policies to build new space technologies and generate the space economy. For example, NASA Space Act of 1958 stated that the NASA missions should seek and encourage the commercialization of the space, and the Commercial Space Act of 1998 stated that the US should plan to use and accommodate the capabilities of the US industries. The NASA Authorization Act of 2005 directed that the Administrators should closely work with private players and try to encourage industrialists who are interested to develop and send the satellites to outer space. “NASA shall make use of US' commercially provided International Space Station (ISS) crew transfer and crew rescue services to the maximum extent practicable”, according to the NASA Authorization Act.[1] And the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 2011, 51 USS and 20112 (a) (4) mandate that NASA work with companies to promote the commercial activities in the space sector. Thus, these are US legal efforts which has opened the windows of private companies to invest in the space sector. These are major acts which have permitted engagement of private players. Several US private companies have been closely working with NASA for the development of space technologies, and launched various satellites for commercial purposes. A report “Public-Private Partnerships for Space Capability Development Driving Economic Growth and NASA’s Mission” which has published by NASA in 2014 provided the details of the public-private partnership. This report studied 8 major areas of public-private partnership; (i) Satellite Servicing—it engages robots to reposition, repair, inspect, rescue and refuel satellite. Two US private companies, Maxar Technologies (MDA) and Alliant Techsystems (ATK) have been providing satellite services; (ii) Interplanetary Small Satellites— these are designed to reduce costs and conduct mission beyond Low Earth Orbit (LEO). They generated over $140 million revenue during the period of 2009-2014. Two US start-ups, Planets Labs and Skybox Imaging started launching small satellites in 2013; (iii) Robotic Mining— it is used to draw, process and transport of materials, and total profit of terrestrial mining was $133 B in 2011. Some companies (Planetary Resources, Moon Express and Deep Space) have declared plans and policies to mine global resources; (iv) Biomedical Sciences—it is focused on discovery of medically significance applications. There are number of companies have invested the biomedical sciences; (v) Liquid Rocket Engines— these are used in launching vehicles and spacecraft that primary manufactured by the two US companies Aerojet Rocketdyne and SpaceX. Through this, US industries generate revenue approximately $ 2.5 to $3 billion annually; (vi) Wireless Power— it is the capacity to transmit power over both long and short distances without wires. The magnetic induction and resonance technologies have been used to transmit power within short distances but for transmission of power over long distances requires microwaves, millimetre waves and lasers; (vii) Space Communication Technologies— these technologies have used to transmit and relay the data between vehicles in space, satellites and assets on the ground; (viii) Earth Observation Data Visualization Technologies— these technologies have used to collect infrared images, thermal imaging, radars and laser pulses. This data helps in scientific experiments, humanitarian, civil and commercial applications.[2] Thus, this report stated that US government had been closely working with private companies to achieve its economic, military and strategic interests. For the US policy makers, space programs can be driving force of the US economy in the 21st century, therefore, they have been consistently focusing on the growth and development of space technologies through the help of the private companies, so that the US can achieve the remarkable progress and develop advance space technologies to compete other major powers in the world.

Russia is one of the countries which has achieved remarkable progress in the space sector. Before 1991, Russian industries dominated the public sector which had developed various advanced technologies during the Cold War period. In 1991, Soviet Union collapsed, and since then Russia did various economic reforms, and permitted private companies' investments in the space sector. During 1991 to 2009, private companies could not achieve much progress. The fundamental change came into the Russian space industry in 2010, when the Russian President Medvedev lunched the ‘Skolkovo Innovation Center’. This centre has permitted the active participation of the private companies for the space sector. This resulted; Dauria Aerospace won a contract to create two small modest space vehicles for the Roscosmos in 2012.[3] Further, in 2014, it built the DX1 satellite for Russia, and Perseus-M microsatellites in the US, which was a remarkable achievement. Similarly, Dauria Aerospace and many other private companies have been contributing for the development and growth of space sector. For example, Gazprom Space company has been working in the fields of communication satellite and earth remote sensing; Sovzond and Skaneks companies provide ground-based ERS services; NIS GLONASS provides navigation services; and Kosmotras offers launching facilities.[4] Thus, it can be said that Russia has invited private companies to contribute for growth of the space sector, like the US.

China's journey in the space sector started in the late 1950s, with the development of the ballistic missile program in response to various threats from global politics. In 2014, China permitted private companies’ engagement in the space sector. Since then, it has made several efforts to develop advanced space technologies for launching satellites and other programs to achieve its long-term economic, military and strategic goals. In the short period, it has achieved remarkable success at the global level. State-owned and private companies have been seriously working to develop advanced space technology so that they can compete with western countries in the space sector. The numbers of Chinese private companies like LandSpace, Onespace, iSpace, Landspace and Expace have been working for the growth and development of space technology. They have contributed in many ways; iSpace and OneSpace have launched a suborbital rocket and LinkSpace conducted vertical landing tests. LandSpace has successfully completed the tests of Phoenix and methane rocket engine/10-ton liquid-oxygen. It has officially declared that its rocket engines have capacity to launch the 3,600 kilograms into a 200-kilometer low Earth orbit or 1,500-kilogram payload into a 500-kilometer sun synchronous orbit, and also have more than 10 times powerful electrons than US and New-Zealand’s small rockets. With this development, China is the third country in the world of which private companies have capacity of developing liquid-oxygen/methane engines.[5] Thus, China has given signals to the US and its allies that it is also an emerging player in the space sector.

France, similar to other advanced countries, has also invited private players to fulfil the requirements of the space sector. The Director General of Armament (DGA) stated that “French military forces have no choice but to move from a conventional procurement toward some kind of public-private partnership for France’s next general military satellite telecommunication systems”.[6] In 2008, the French government passed the Space Operation Act which has provided the legal framework of the private player engagement in the space sector.[7] Kinéis is one of the start-ups which had formed in 2018 to achieve the nano-satellites. It has formed a commercial partnership with Suez, Bouygues Telecom, Arribada and the Wize Alliance[8]. Thus, it can be said that the efforts of the French government have positively contributed in the growth of the space sector. So, these are the major countries which have permitted the private players’ engagement in the space sector. They have been trying to increase their space technologies' capabilities to deal with economic, military and strategy issues. They have been looking at space economy as one of the emerging economies that need to be expanded.

India can learn from above countries, and start to make an environment for establishing space infrastructure and invest on research and development activities. The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) also felt that it required private partners who could help overcome some challenges like a shortage of manpower and limited financial resources. Keeping that in view, the Indian government has permitted private companies to invest in the Indian space sector and work with ISRO to achieve long-term industrial, economic and technological objectives. This announcement and policy reforms is based on Dr A. Sivathanu Pillai’s committee report which was constituted two year ago, headed by the eminent aerospace scientist Dr A. Sivathanu Pillai. This committee suggested that IRSO can be open for the private companies in a gradual manner. It was also suggested that ISRO should focus on the development of large and heavy satellites leave the rest of mini and micro satellites to the private companies, which will overcome the burden of ISRO. The arguments of the committee was also repeated by the Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharaman during the press conference where she said that private companies will likely play an important role in satellites, launches and space-based services. She also added that many Indian companies have been developing space technologies, but unfortunately, due to the existing government policies, private players could not use ISRO facilities. Now, the Government has changed the existing policy and permitted private companies to invest in the Indian Space Sector. This policy reform evolved a new debate among the policy makers. They started debating the forthcoming impacts of engagement of private companies in ISRO. They supported the private companies in the ISRO. They also added that ISRO has largely contributed for the national development since its establishment and achieved the objective of prominent nuclear scientist, Vikram Sarabhai, who established the institution in 1962. Since then, it launched a number of satellites, vehicle projects and executed many application programs for national progress and governance that built a positive image of India among the major advanced space technology countries. The government’s new policy reforms and allowance of private players will have a larger impact on the growth and development of the space sector. As Nitin Pai, co-founder and director of The Takshashila Institution argued that “India must deregulate the space sector to encourage private enterprises if we are to compete in the new space economy”.[9] Rajeswari Pillai Rajagopalan, Distinguished Fellow and Head of the Nuclear and Space Policy Initiative at Observer Research Foundation stated that “China wants a share of the global commercial market, estimated to be worth around $350 billion (Rs 26.46 lakh crore). If ISRO does not improve its launch infrastructure and increase the number of launches, it will be at a disadvantage. And despite India’s cost advantages, it has a mere 2% share of this, worth $7 billion. India can gain significantly if ISRO and the country’s private space sector can cooperate effectively and synergistically”.[10] The former ambassador Rakesh Sood stated that India should create a suitable policy environment for the participation of the private players which would help in overall growth of the space sector.[11] Narayan Prasad and Prateep Basu argued very closely to Rakesh Sood's argument; they said that India has missed the utilisation of global opportunities of the space sector due to lack of policy guidelines and regulations, therefore, India needs to structural policy reforms for the private enterprises to play an important role in the local and global market.[12] Almost all of them have focused the policy reforms so that Indian space can get benefits global opportunities. But some issues are not yet clear, and it remains to be seen how the government will respond to that; (i) issue of intellectual property rights that has been discussing among the policy makers. Private companies are not feeling comfortable with the existing government policies; (ii) method of private companies’ engagements with the government agencies and how they will engage with each other. The issue of private companies autonomy remains to be discussed, because private companies have a serious concern about autonomous regulation; (iii) secrecy is one of the foremost concerns of ISRO; ISRO and private companies will share the information among the scientists and other professionals, but how they will protect important information remains to be seen (iv) the process of legalization is still missing. Space Activities Bill is pending in which the detailed explanations of the method of private companies engagements, licensing and procedures including eligibility criteria, terms and conditions, responsibilities and punishments, but this bill has not been yet passed by the Indian Parliament. If the government passes this act, it will largely help in overcoming challenges like budgetary limitations and manpower, and also help to make ISRO strong, capable and competitive like other global space agencies, which will help in fulfilling India’s forthcoming requirements and generate space economy. These are some challenges which can be overcome by doing some constructive efforts. If India wants to compete at the global level, it should try to make an industry-friendly environment for the growth and development of Indian space sector.

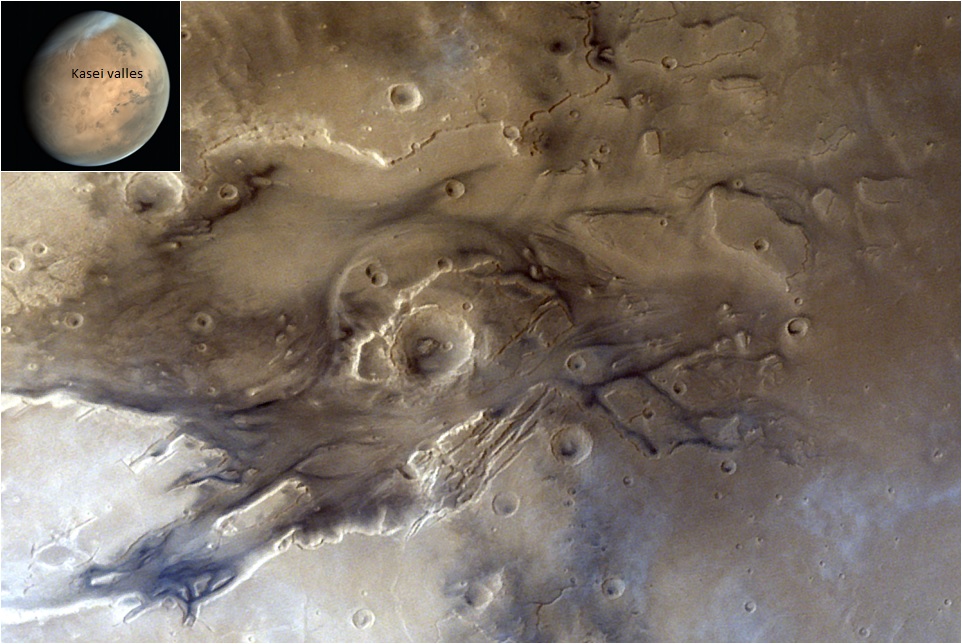

Picture Courtesy-ISRO Website(Mars Pictures)

(Alok Kumar is Guest Faculty at Department of National Security Studies, Rajiv Gandhi University (Central University), Itanagar, Arunachal Pradesh. He has been working on US-India Defence Engagements, Defence Technology Transfer and Foreign Direct Investment in the defence sector. The views expressed are personal)

Notes

[1] Martin, Gray and Olson, John (2020), “Commercialization is Required for sustainable space exploration and development”, available at https://ntrs.nasa.gov/archive/nasa/casi.ntrs.nasa.gov/20100027548.pdf (accessed 05 June 2020).

[2] MacDonald, Alex (2014), “Public-Private Partnerships for Space Capability Development Driving Economic Growth and NASA’s Mission”, available at https://www.nasa.gov/sites/default/files/files/NASA _Partnership_Report_LR_20140429.pdf (accessed 08 June 2020)

[3] McClintock, Bruce (2017), “The Russian Space Sector: Adaptation, Retrenchment, and Stagnation”, available at https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/external_publications/EP60000/EP67235/RAND_ EP67235.pdf (accessed on 10 June 2020).

[4] Zhukov, Sergey and Mikhail, Kokorich (2014), “Skolkovo and a new breed of Russian space start-ups”, available at https://room.eu.com/article/Skolkovo_and_a_new_breed_of_Russian_space_startups (accessed 13 June 2020)

[5] Curcio, Blaine and Lan, Tianyi (2018), “The rise of China’s private space industry”, available at https://spacenews.com/analysis-the-rise-of-chinas-private-space-industry/ (accessed on 14 June 2020)

[6] Selding, Peter B. De (2013), “Public-private Partnership Assured for France’s Syracuse 3 Successor”, available https://spacenews.com/public-private-partnership-assured-for-frances-syracuse-3-successor/ (accessed on 15 June 2020).

[7] Available at https://www.unoosa.org/pdf/pres/lsc2009/pres-04.pdf (accessed on 15 June 2020)

[8] Tucker, Charlotte (2020), “French startup Kinéis raises €100 million to launch its IoT nanosatellites constellation into orbit”, available at https://www.eu-startups.com/2020/02/french-spacetech-startup-kineis-raises-e100-million-to-launch-its-iot-nanosatellites-constellation/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

[9] Pai, Nitin (2020), “Some space for the private sector in the race for space”, available at https://www.livemint.com/opinion/columns/opinion-some-space-for-the-private-sector-in-the-race-for-space-1563732806415.html (accessed on 17 June 2020).

[10] Rajagopalan, Rajeshwari Pillari (2020), “India’s Space Programme: A role for the private sector, finally?”, available at https://www.orfonline.org/research/indias-space-programme-a-role-for-the-private-sector-finally-66661/ (accessed on 16 June 2020).

[11] Sood, Rakesh (2019), “Expanding India’s Share in Global Space Economy”, available at https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/expanding-indias-share-in-global-space-economy/article28286469.ece (accessed on 16 June 2020).

[12] Prasad, Narayan and Basu, Prateep (2015), “Space 2.0: Shaping India's Leap into the Final Frontier”, available at https://www.orfonline.org/wp-content/uploads/2000/10/OccasionalPaper_68.pdf (accessed on 18 June 2020).